If you want to create comics, I think Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics is required reading. “But Jim! I’ve read enough comics to understand them! I don’t need to read this!” Well, if you’ll allow me a sports metaphor… Watching Michael Jordan or Lebron James play hundreds games isn’t gonna make you a great basketball player, nor is watching every NFL game on Sunday gonna make you a great coach. In short, there’s a lot of doing the work and studying the craft involved in mastering the craft, so if you want to create comics, you should do more than just read lots of comics, you should immerse yourself in information about the craft.

But, getting off my soap box (“He said, while writing am advice-centric blog post.”), I’m writing this post about two pages from Understanding Comics that I think are a great lesson for newcomers and a fantastic refresher for old pros alike.

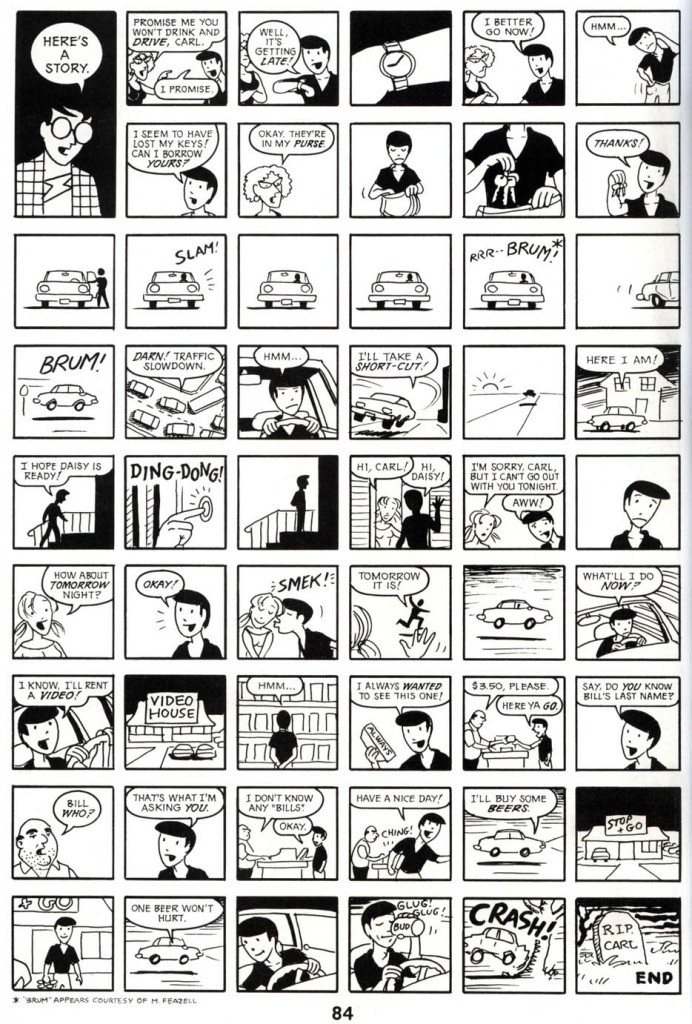

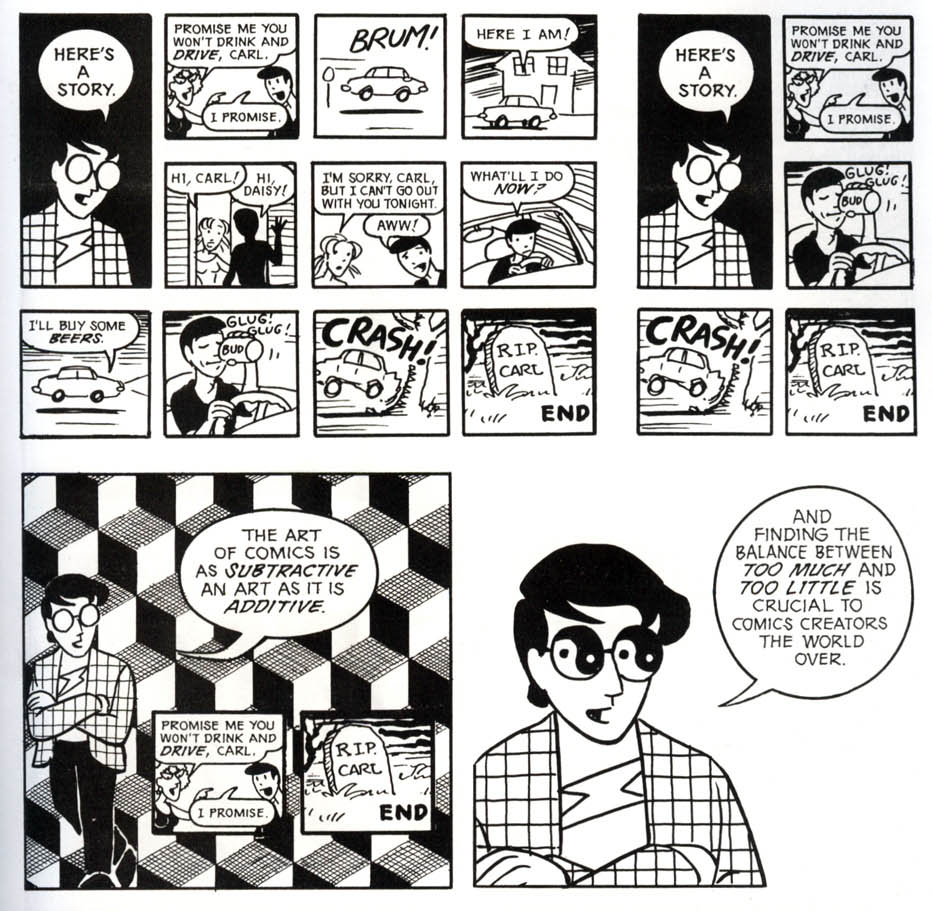

In Chapter 3, McCloud talks about how the space between two panels (the gutter) is a storytelling gap bridged by the mind of the reader. If you show an axe coming down on a guy in one panel and then cut to a cityscape with a scream echoing through it, to use McCloud’s example, you presume the axe has found its mark and the victim has been killed, even though you didn’t see it. McCloud, among other genius explanations of the gutter’s unique capabilities and uses (Seriously, go read this book!), goes on to show how the ability of comics to force readers to make that leap between panels makes comics a—again, as he puts it—an additive or subtractive art.

(Images snagged from here.)

Now, these four different stories use the same imagery and text but vary in length. By adding or removing the panels, McCloud shows that an audience can be led to the same conclusion with as few as two panels. Readers can fill in the gap between the gutters and find the closure he talks about throughout the chapter—the brain connects the dots between the first and final panel regardless of how many panels are shown between the two.

However, another thing I notice when I read these pages is that each of the four versions of this story tells, I think, a slightly different story. Each begins with a warning not to drink and drive and ends with a dead Carl, but the journey that gets us there in each tells a unique tale. For example, the second version can be interpreted as a story in which rejection causes Carl to drink and drive, while the third story simply shows Carl making the poor choice of drinking and driving. In the fourth version, the two panel version, maybe Carl is the sober driver but ends up killed by a drunk driver. A lot of the same images and words, but I see four distinct takes on a similar idea.

And, because of that, McCloud’s final point really sticks with me…

How many times have you read a story where you felt the author was killing time? How many times have you read a comic book series where one issue felt like filler? Or a miniseries where you finished the story and thoughtt, “That didn’t need six issues. They could have told that story in four.”? Conversely, how many times have you read something in which the added detail and the ambling nature of the storytelling led you to focus on the journey more than the destination? McCloud shows four versions of a story. Neither one of them is right or wrong. All of them are valid. But, they all tell a slightly different story.

Which brings me to my point…

Figure out what story you’re trying to tell first, then write or create it.

Is it a cautionary tale? A story about a tragic breakup? A anecdote about a guy in the wrong place at the wrong time? Or is it the saga about how one man’s life has, over time and through countless scenes and a plethora of decisions, led him to drink a beer while driving? And, in the end, what’s the point you’re trying to make?

Once you know what your story is about, it’ll be much easier to figure out how long it should be. It will be easier to figure out what scenes you need and how you should pace your story. It will be more obvious when a character or a scene is unnecessary. It will give you an anchor, something that reminds you what the point is so you can help yourself stick to it. It will help you separate the wheat from the chaff. It will help you make it good, maybe even great, instead of just long.

You can get even more specific with this too, as it will help you cut extraneous subplots, unnecessary panels, and verbose dialogue. It’s the watch words that you go back to with every aspect of the story and go, “Is what I have here helping me tell my story?” If it’s not, well… cut it. Or rewrite it. But probably cut it. It’s your plan. Stick to it. Your story will be better for it!

McCloud’s right. Finding the balance between too much and too little is a crucial part of comics. Sort out what story you’re actually telling, and you’ll be one step closer to getting the story length just right.